DANCE DANCE EVOLUTION

Writer Luke Ryan tells us why Leon Vynehall stands at the forefront of dance music's political moment.

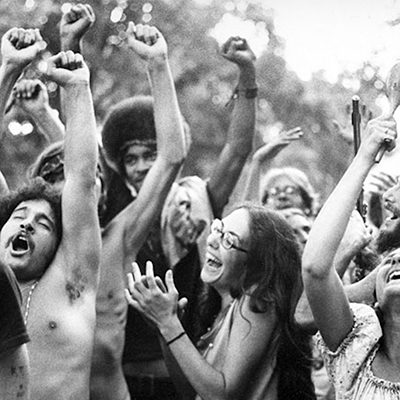

Exactly thirty years ago, in what became known as the UK's Second Summer of Love, modern dance music burst into existence in a sweat-drenched frenzy of acid squelches, hypercolour fashion and unlicensed, MDMA-fuelled rave parties. Against a backdrop of Thatcherite austerity and social breakdown, rave culture felt like the ultimate escape, an apolitical movement dedicated to hedonism, aural excess and the overarching principle of PLUR: peace, love, unity, respect.

It was an intoxicating dream, in more ways than one, and one whose deliberate naivete was its greatest drawcard. The subsequent years witnessed a Cambrian explosion of new styles, acid house giving way to jungle, hardcore, trance and rave, each attracting fervent devotees and ever more precise sub-generic classifications. (Progressive house or deep house? You tell me.) But the profusion of new forms obscured an insularity at dance music's heart. Sure, it was fun, but what did it actually mean in the harsh light of dawn?

For a lover of electronic music, the scene's unwillingness to grapple with the questions of representation, diversity and privilege that the rest of the world were busy with could leave one despairing. It's hard to watch the arrival of Brexit and the ascension of Donald Trump and still believe in the inviolable purity of the dancefloor.

However now a new wave of producers are starting to think more deeply about the possibilities and politics of dance music. UK producer Leon Vynehall's 2018 opus Nothing is Still is a calling card for a more expansive, meaningful understanding of house music.

An artist who cut his teeth on jazz-infused, off-kilter house, Vynehall's music has always been wide-ranging in its references, even as it kept its eyes squarely on the dancefloor. His first two albums – 2014's Music for the Uninvited and 2016's Rojus – were expressions of technical mastery, collections of impeccably designed club-ready cuts loosely tied together by a shared sonic palette.

But on Nothing is Still, Vynehall inverts the equation; the shared palette reigns and the house is subservient. Based on stories his grandmother told him of her emigration from Southampton to New York in the 1960s, the music on Nothing is Still speaks to the dislocation, discovery and longing that comes with the immigrant experience.

Storytelling has never been dance music's strength, but Nothing is Still unfurls like a novel, nimbly traversing noise and quietude, ecstasy and despair, claustrophobia and freedom across the course of its nine "Chapters". Long gone are the adrenalised thrills of Vynehall's early output. Here each track unfolds with the unhurried tempo of a reverie, melancholic strings and glistening pianos drifting together with burbling bass and snatches of murmured conversation.

The tropes of house music are unmistakably present: they've just been refashioned and repurposed. Working with his friend Max Sztyber, Vynehall created a novella of the same name to give voice to the story of Nothing is Still. The two works exist in symbiosis, offering context and depth to each other while revelling in the contradictions and uncertainties that live in the stories we tell.

Nothing is Still isn't political, per se. There are no rousing anthems or searing diatribes; Vynehall isn't calling us to the barricades. But over these forty minutes he makes a compelling argument for a more considered electronica, one awake to the diverse ways we might come to the dancefloor, and what we might hope to find there.

Dance music may not save the world, but through albums like Nothing is Still it can cause us to think more deeply about our place within it.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: LUKE RYAN

Luke Ryan is a Melbourne-based freelance writer and comedian. He is the editor of the Best Australian Comedy Writing series and author of A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to Chemo, a comedy memoir about having had cancer a couple of times, out through Affirm Press. His work has appeared in numerous publications including Best Australian Essays, The Guardian, Quartz, Smith Journal, The Lifted Brow, Junkee, Crikey, Kill Your Darlings and many more.

Discover more about Luke on his website

Follow Luke on Twitter

Read more on Luke's blog