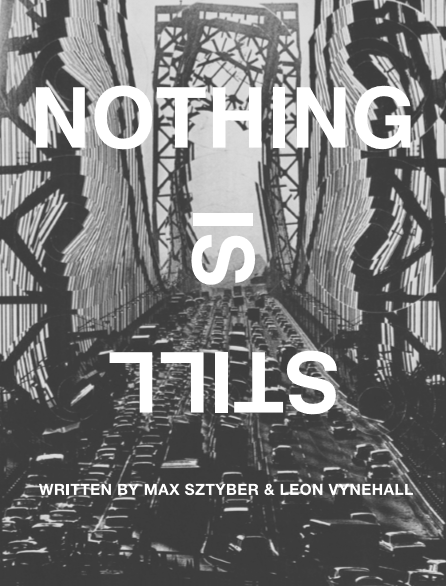

EXCERPTS FROM LEON VYNEHALL'S 'NOTHING IS STILL' NOVELLA

The literary companion to Leon Vynehall's electronic masterpiece.

Nothing is Still is an immersive concept album by British DJ/Producer Leon Vynehall which embraces the blurry lines between family history, memory and fiction. It is inspired by the true-life experiences of Vynehall’s grandparents and their emigration from England to New York at the beginning of the 1960s.

It was while Vynehall was working on his 2016 release Rojus and relocating from Leicester to Brighton that his grandfather passed away. While spending time with family following his grandfather’s death, his Nan began recounting stories of their life journey together, which sparked something inside him. What began with polaroids and anecdotes from his Nan evolved in a way Vynehall never quite imagined. Vynehall felt the deep need to create something from their remarkable stories. A collaboration with his friend Max Sztyber followed and together they began drafting what would become the Nothing Is Still novella, a literary companion piece to the album.

The novella is told from the perspective of Stephanie, a new mother struggling to find a sense of place and purpose in an American Dream she no longer recognises as her own. Stuck between mid-century America's overbearing optimism and sinister contradictions, Stephanie begins to lose the plot of her own life story and longs for the comfort of her family and home. Through her vulnerable and compassionate gaze that readers can observe America as it was, and in many ways, still is.

Read an excerpt from Chapter 1 - From The Sea below.

CHAPTER I. – FROM THE SEA

Friday, 11 October 196

No journey starts or ends. Journeys only unravel outwards. Our car slips off a gradually sloping gravel driveway and onto a long, winding stretch of road. Rolling fields run forever in every direction, with square swarms of crêpe-paper poppies and oilseed breaking up the masses of green; patchwork territories bordered by teeming hedgerows, broken occasionally by wooden gates and stiles. Doll’s houses hug the tops of the hills and cling tight to the secrets of their inhabitants’ lives. Cirrus clouds, Brillo-pad brushstrokes of white, hang dead straight in the sky above: I can’t feel it yet, but the wind’s either with us or against us. Only time will tell. The scene unravels out from the middle. I can’t recall where this road is, but I know it was thrown down hastily during the war to swiftly bypass a nearby town. It chicanes left and right to make way for an ancient yew with its twisted trunk open and its insides bare. The road is laid in a series of slabs that jolt the back seat of the car in a slow-spoken rhythm, each rough bounce betraying my father’s calm lack of desire to get to where we’re going.

The smell of somewhere I’ve been before fills the car, on this road to nowhere. I recognise the shapes of the conifers in the distance leaning into the absent breeze; I remember the way the sunburnt reeds of grass fall away to our left into the shallow valley, filled with the buzz of crickets; but still I can’t place it, I can’t remember where this belongs.

In front of me, my father’s hatless head babbles away, spouting words that gurgle into meaninglessness between my ears. The cadences are definitely his, though, and make me feel somehow safe and at home. At the same time, that strange notion that sometimes haunts you for no particular reason – the one that tells you that whatever you’re doing, this is the last time you’re doing it – is as palpable as the leather-covered cut-foam seat squeaking beneath me every time the hard rubber tyres thump over the joints of the road.

My father carves through the oil-on-canvas countryside, easing through countless gears that never seem to break the rhythm of the slabs. Hup. Hup. Hup. Hup. The air smells like summer: sweet and weak and important. I know this journey, I know this place, but before I can work out where we’re going, the dream, the first and only one I’ve had since leaving England, loses me. It breaks. The car and the countryside around me unravel until they are no more.

I am six days and five nights into a week-long journey by boat and I am seasick. I’ve been bound to this bed like it’s magnetic; I’m foetal, trembling, delirious, and all I know is this room, as if I’ve been born into a whale-belly prison, held for a lifetime at the pleasure of the Atlantic Ocean, and everything I remember is just a hazy web of half-forgotten fantasy.

The heavy, guttural hum of the ship’s engines floods the cabin and reverberates off its shuddering timber-clad walls, waltzing in the air with the violent and sour stench of sick. The noise, like going underwater in the bathtub, feels like fingers in your ears and squeezed-shut eyes.

It didn’t take long for the sickness to shut down my digestive system. We weren’t an hour out of port when the first wave of nausea swept through me, forced me down into this room, a tin bucket with half an inch of cold water in the bottom for company. Derick sat with me through the first day and night but I had to stand him down. Suffering alone seems harder in the presence of others. Besides, there’s nothing he can do for me.

After that dreadful first night, unable to keep food down, abdominal muscles already sore, I was brought cold slices of Jaffa orange to suck on by the crew. Pectin for the nausea, ascorbic acid for nutrition – an old trick, apparently – but the sweet, sticky citrus triggered the bleachy, animal taste of sick about to come and my body contracted, rejecting it. All hope I had of some form of relief joined the flood at the bottom of the bucket. The fingernails I’d especially manicured for the newspaper photographer and have since bitten to the quick are as much as has passed my lips, save for a lonely triangle of dry toast and the little water that stayed sipped.

Derick checked in on me again this morning, not long after I’d woken up. My lips are cracked and stuck to my front teeth. I let him talk rather than say anything. He told me the temperature on deck has dropped sharply, that the sky and the air are completely clear, that the stars at night look close enough to make you think the whole universe is in the palm of your hand.

In between games of shuffleboard, the Polish sailor he’s been sharing cigarettes with said that we’re almost close enough to see the coastline of Nova Scotia in the distance. The rocks there are littered with colonies – like cities – of puffins. You can hear gannets and seagulls circling high above us, Derick says, on the lookout for morsels of fish in the icy water, and it’s not uncommon to encounter schools – are they schools? – of dolphins and even humpback whales at this time of year.

The day we left I had to wonder if the boat, the SS New Amsterdam, wasn’t his Hispaniola. Derick never really talks about the books he’s read, as a boy or a young man, so I don’t know what his childhood fantasies were, but as we boarded amidst the hiss of flashguns, his smile broke through everything overcast or grey. I’ve never seen him happier.

The East Grinstead Courier sent a journalist and a photographer down to Southampton to meet us. The former was a large, laconic gentleman who sighed through his nose after every sentence and constantly made slow and minor readjustments to his struggling braces. He took our answers down in longhand and let his partner – a skittish photographer, seemingly half his size – ask us all the questions. The only part of him that kept still behind the camera was his black, Brylcreemed hair, and it was hard to imagine how the pictures didn’t come out all blurry.

My nails were perfect. I spent the morning painting them and sculpting my hair, fussing over loose strands in a fug of talc. I wore my best dress, in a shimmering green and gold that almost matched the ship’s smokestacks. It rode my thighs slightly higher than either of my other two dresses. I’d tried all three on, two or three times each.

Flash, flash, flash. The glare of the sun like the lights of Broadway, we squinted back at the immovable pompadour behind the lens. We posed awkwardly and gave gauche answers to all the questions of where and why we were going and what we expected, but still we soaked up the day’s action indulgently. Before then, our pilgrimage – our pioneering – hadn’t felt real, but the day’s fame and the almost-unbelievable actuality of the boat gave it gravity, made it concrete. My dress was hung up and replaced by a dressing gown by the time the bucket was set down by my bedside. It was lucky to escape unscathed. That feels like forever ago. We must be close to New York now. As close as the engines are to this cabin, and yet as far as the end of the hallway from the peephole of a door. It’s that Christmas Eve feeling. So close. So far.