Steven Isserlis & Charles Owen

This July, Steven Isserlis and Charles Owen take to the Elisabeth Murdoch Hall stage to perform as part of Melbourne Recital Centre's International Classics series. Explore the program in this excerpt from the official program notes, written by Phillip Sametz.

About the Music

You might think violinists could be a little smug about the Beethoven sonata situation. Beethoven composed his ten sonatas for violin and keyboard between 1797 and 1812. The first of them precedes the Symphony No.1 by two years, and the last was completed in the same year as the Seventh and Eighth symphonies. The cello sonatas, although fewer in number, cover a greater span of Beethoven’s creative life; the first two, from 1796, come not long after the Second Piano Concerto, while the final two precede his song cycle An die ferne Geliebte by a matter of months. Through the course of five sonatas you journey from the music of a confident young pianist to that of a composer gazing at new, far-off musical horizons.

The first cello sonatas are notable for another reason: they represent a new kind of music for the instrument. In the young Beethoven’s day an ‘accompanied keyboard sonata’ meant that a capable pianist would be joined by a subservient melody instrument (usually flute or violin). But as Beethoven once wrote to his publisher: ‘I cannot write anything non-obbligato, for I came into this world with an obbligato soul.’ In other words, the idea of writing an optional (ad libitum) part was anathema to him. From the first bar of the Op.5 sonatas, it’s clear that the two instruments enjoy a shared glory. Moreover, these are the first significant cello sonatas with a fully notated keyboard part; in other words, you’re listening tonight to the creation of the modern cello sonata, an event as momentous in the world of chamber music as the publication of the first piano quartet – Mozart’s K.478 – of a decade earlier. (The proximity of these two ‘inventions’ may be aligned with the rapid advances in keyboard technology, but that’s a subject for another day).

Beethoven first performed the keyboard part in these sonatas in exalted circumstances when, as part of an extensive concert tour, he stopped in the Prussian capital, Berlin, and met King Frederick William II. Like his uncle, Frederick the Great, he was a keen music-maker, but unlike the flute-playing Frederick, his instrument was the cello. (Haydn, Mozart and Boccherini, among others, had written works for him). He also had in his employ at court two outstanding French cellists who were also siblings: Jean-Pierre and Jean-Louis Duport. Beethoven wrote his Op.5 sonatas especially for his visit to Berlin, and on one of the many occasions on which he played for the King, introduced these works with one of the Duports (which one exactly is not recorded). Frederick William must have been impressed, because he gave Beethoven a gold snuff box filled with French gold coins (Louis d’or). Beethoven subsequently dedicated the sonatas to the Prussian monarch.

As with so many other musical genres, from the concerto to the string quartet, Beethoven’s tendency was for the transformative. Sure enough there is very little about the Op.5 sonatas that would have been considered conventional at the time. Notably, they are both, in effect, in two movements, with extended Adagio introductions opening out onto epic Allegro movements before each work concludes with a rondo finale. The first sonata is, on the whole, boisterous and good-humoured, with a rich vein of lyrical poetry; while the second, which you hear tonight, is far more dramatic. The long-breathed introductory Adagio, suspenseful and darkly beautiful, appears to take a deep breath before giving way to the tempestuous Allegro. In this context, the final Rondo movement seems exceptionally jaunty. If you’re familiar with the Beethoven of the Waldstein Sonata and Eroica Symphony (both from 1804), you may not be surprised at the scale of the opening movement, but no duo sonata up to this time contained anything this ambitious.

Beethoven subsequently performed these sonatas with cellist/composer Bernhard Romberg, a figure later admired by Brahms. ‘You should know,’ Brahms wrote to the cellist Julius Klengel, ‘that we are close colleagues. As a boy I too played the cello, and even managed a concerto by Romberg.’ Brahms lived through a scientific age of systematic music publishing and cataloguing; such publications were major events for him, and you can hear his veneration of Bach, Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven in his own music. These composers were part of his lived experience as a composer for, as author and administrator Nicholas Kenyon has put it, Brahms was ‘absorbed by the tradition he had inherited from music’s past, reluctant to reject it but rather working to renew it.’ And his first cello sonata, which he began in his 20s, includes a Mozartian minuet and a fugal finale directly inspired by Bach.

The second sonata is a different beast, for although you could describe the passion of the opening Allegro vivace as Beethovenian, it’s worth recalling the words of Brahms’ biographer H.C. Colles: ‘There is a story at the back of all Brahms' great works, but it is a personal story, not a dramatic one.’ And while tradition is being renewed in this work, this renewal takes place on deeply personal terms. The emotions in the first movement are tempestuous, the two instruments often hurling ideas at one another, before a coda which suggests that all might end calmly – until it doesn’t. The Adagio affettuoso has the burnished gold quality which so often glows from Brahms’ later music. The cello’s singing line, so not apparent in the previous movement, blossoms here when the cello takes up the main theme. The Allegro passionato does what it says on the tin, its moments of darkness recalling the writer Bayan Northcott’s observation that in much of Brahms’ later music he seems to be ‘asking himself, in his lonely eminence, if things could all have turned out differently’. The short, sometimes impish finale acts as a kind of counterweight to the passions of the preceding movements. It’s hard to think of an outwardly well-behaved, classically constructed sonata of this period in which the composer detonates so many emotional explosions.

The most popular work by Czech composer Josef Suk is his early, sunny Serenade for Strings (1892), composed at the urging of his composition teacher and father-in-law Dvořák. But the emblematic work of his life is the searing Asrael Symphony (1904-06), created as a result of unimaginable tragedy – the deaths of Dvořák, and Dvořák’s daughter, Suk’s wife Otýlie, within a year of one another. Although the Ballade and Serenade originally date from Suk’s 16th and 17th year respectively, you can hear them as a yin and yang of tragedy and cheerfulness. They are his only works for cello and piano.

Even if Martinů only spent the first 33 years of his life in his Czech homeland, his music tells you that it remained his spiritual home for the rest of his life. He left Prague for Paris in 1923 on a scholarship to study with the composer Albert Roussel. France became his home for the next 17 years, but with the German invasion Martinů and his wife Charlotte fled to the United States. After WWII he returned to Europe, living variously in Nice, Rome and finally in Schoenenberg, Switzerland. Declared persona non grata first by the Nazis then, after 1948, by the Communists, he never returned to Czechoslovakia during his lifetime; his remains were repatriated in 1979.

The ‘second second’ in tonight’s program is also the second of Martinů’s three sonatas for cello and piano, and dates from 1941, his first year in the USA. On arrival, he was befriended by the Czech cellist and former Janáček pupil Frank Rybka, who helped find the Martinůs a flat in his neighbourhood of Jamaica, Long Island. The two families became close and Martinů dedicated this sonata to his new friend.

The work is powerful, concise and, like so much of Martinů’s music, full of energy. The sparks fly frequently between the two instruments in the opening Allegro, while the final Allegro commodo features rhythmically vibrant ideas that suggest the world of Bohemian folk dancing, the festivities here being halted only by a short cello cadenza. But the heart of the sonata is the central Largo, in which it’s hard not to hear the turbulence of the times – and the personal circumstances – in which Martinů composed this music. He could not have known at this point that he would never see the land of his birth again.

©Phillip Sametz 2023

About the artists

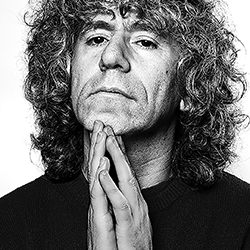

Steven Isserlis

Acclaimed worldwide for his profound musicianship and technical mastery, British cellist Steven Isserlis enjoys a uniquely varied career as a soloist, chamber musician, educator, author and broadcaster. He appears with the world’s leading orchestras and conductors and gives recitals in major musical centres. As a chamber musician, he has curated concert series for many prestigious venues, including London’s Wigmore Hall, New York’s 92nd Street Y, and the Salzburg Festival. Unusually, he also directs chamber orchestras from the cello in classical programs. Steven’s wide-ranging discography includes J.S. Bach’s complete solo cello suites (Gramophone’s Instrumental Album of the Year), Beethoven’s complete works for cello and piano, concertos by C.P.E. Bach and Haydn, the Elgar and Walton concertos, and the Brahms double concerto with Joshua Bell and the Academy of St Martin in the Fields. The recipient of many awards, Steven’s honours include a CBE in recognition of his services to music, the Schumann Prize of the City of Zwickau, the Piatigorsky Prize and Maestro Foundation Genius Grant in the U.S., the Glashütte Award in Germany, the Gold Medal awarded by the Armenian Ministry of Culture, and the Wigmore Medal

Charles Owen

Charles Owen enjoys an extensive international career performing a wide-ranging repertoire to outstanding critical acclaim. He appears at many major UK venues such as Wigmore Hall, Bridgewater Hall, The Sage, and Kings Place. Internationally, he has performed at Lincoln Center and Carnegie Hall in New York City; the Brahms Saal in Vienna’s Musikverein; Paris Musée D'Orsay; Amsterdam Concertgebouw; and the Moscow Conservatoire. His chamber music partners include Julian Rachlin, Alina Ibragimova, Steven Isserlis and Augustin Hadelich as well as the Takacs, Carducci and Vertavo Quartets. His piano duo partnership with Katya Apekisheva has received widespread recognition. Together they are Co-Artistic Directors of the London Piano Festival held annually at Kings Place since 2016. Charles Owen is a Professor of Piano at the Guildhall School of Music & Drama, London and Guest Professor at RWCMD, Cardiff. He was appointed Steinway & Sons UK Ambassador in 2016 and is also an Ambassador for the Help Musicians Charity

Click here to discover more about Steven Isserlis and Charles Owen's International Classics recital.

You might also be interested in

-

-

-

Explore the program notes in advance