Jayson Gillham – Bach & Chopin

On Monday 6 June, Jayson Gillham takes to the Elisabeth Murdoch Hall stage to perform works by Bach and Chopin as part of Melbourne Recital Centre's Great Performers series. Explore the program in this excerpt from the official program notes, written by Stella Joseph-Jarecki.

Internationally praised for his compelling performances, Australian-British pianist Jayson Gillham is recognised as one of the finest pianists of his generation. He performs with the world’s leading orchestras with recent highlights including engagements with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, Bournemouth Symphony, Sydney Symphony, Melbourne Symphony, Adelaide Symphony, West Australian Symphony, Auckland Philharmonic, Christchurch Symphony, London Philharmonic Orchestra, English Chamber Orchestra amongst many others.

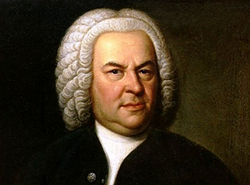

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) | transcr. Petri (1881-1962)

Sheep May Safely Graze, BWV 208

This program is entirely built around interpretations of dance forms, with the exception of Sheep May Safely Graze. This piece originally appeared as a soprano aria in Johann Sebastian Bach’s secular cantata Was mir behagt, ist nur die muntre Jagd (The lively hunt is all my heart desires). The cantata was written to commemorate the 31st birthday of Duke Christian of Saxe-Weissenfels and to extol his virtues as a leader.

Sheep May Safely Graze draws parallels between a shepherd tending to his flock, and a capable leader ruling over his subjects: ‘Sheep may safely graze/ Whilst the shepherd is watching/ Where the wise and good rule/ Peace will also reign there/ And there will be peace throughout the world’.

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750)

Partita No.1 in B-flat, BWV 825

A partita is a suite of dance forms in the same key, following a core sequence of an allemande, courante, sarabande, and gigue. This formula could be expanded with a prelude, and elaborate dances such as minuets and gavottes in the penultimate position.

Partita No.1 was one of the first pieces published in Bach’s lifetime, despite the fact the composer was in his early forties at the time and had written a staggering mountain of music in the decades prior. This output included over 200 organ pieces, 200 cantatas, the Brandenburg concertos, and suites, sonatas, and concerti galore.

Bach produced six keyboard partitas between 1726 and 1731 and published them in a volume under the unassuming title of Clavier-Übung (keyboard exercise). While that might call to mind bland, repetitive exercises designed to drill a specific technique into the hands of the student, Bach’s keyboard partitas are certainly not lacking in character.

Partita No.1 is a vibrantly upbeat composition. The opening praeludium smoothly moves through trills and stepwise motions with unhurried elegance. This is followed by an allemande that barely stops for a breath with cascading, unbroken streams of semiquavers. The third dance is a brisk Italian corrente in place of a French courante. A sarabande brings a dignified change of pace with an air of introspection. Two succinct menuets precede the final movement: a vivacious gigue which joyfully bounds from one side of the piano to the other.

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) – transcr. Busoni (1866-1924)

Violin Partita No.2 in D minor, BWV 1004

Bach’s collection of partitas for solo violin were completed sometime between 1717 and 1720. Tragically, in 1720 Bach returned home from a short business trip to the news that his wife Maria Barbara had died and the funeral had already taken place. It is not known for sure whether the violin partitas were completely finished by this time, or if Bach channeled his emotions into his work.

Violin Partita No.2 follows the set partita structure, running through an allemande, courante, sarabande, and gigue. A striking point of difference is the movement rounding out the piece: a chaconne. The chaconne started life as a fiery dance in Spain and Mexico and is thought to have arrived in Europe with Spanish explorers in the 16th century. Over time the chaconne evolved into a stately musical form built on a repeated bass figure, commonly heard in the French aristocratic courts.

The chaconne alone is longer than the partita’s preceding four movements combined. The harmonic pattern which forms the foundation of the movement is only four bars long, and Bach masterfully draws out 64 variations on this motif. The first 33 are written in a minor mode, followed by 19 in a major mode, with the final 12 circling back to minor. The sheer variety of textures within this structure have captivated listeners for centuries.

Johannes Brahms was in awe of the vast landscape traversed by Bach within only fifteen minutes: ‘On one stave, for a small instrument, the man writes a whole world of the deepest thoughts and most powerful feelings. If I imagined that I could have created, even conceived the piece, I am quite certain that the excess of excitement and earth-shattering experience would have driven me out of my mind.’

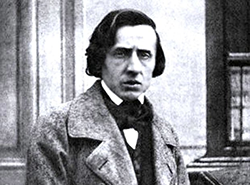

Frédéric François Chopin (1810-1849)

Etudes, Op.25

Frédéric François Chopin penned two collections of etudes between the tender ages of nineteen and twenty-five. His first collection, Op.10, was dedicated to his friend and fellow piano virtuoso, Franz Liszt. By the time Chopin was composing the twelve etudes of Op.25, he had gained a reputation as an exceptional piano teacher in Paris.

Etudes were traditionally designed to sharpen a pianist’s proficiency in a particular technical area. Whether they were musically interesting to play was another matter- but Chopin’s etudes never lacked for textural interest or emotional nuance. Concert pianist Garrick Ohlsson attests that ‘If you can play the Chopin Etudes… there is basically nothing in the modern repertoire you can’t play’.

Etude No.1 has been given the nickname ‘Aeolian Harp’, after a stringed instrument which produces sonorities when brushed by the wind (named so after Aeolus, Greek god of the winds). It should be noted that Chopin never gave his pieces descriptive names- these were added by enthusiastic publishers and fans. The main melody of the etude floats on top of an undulating sea of arpeggios. The technical challenge of this piece is one of phrasing- the notes should smoothly flow on from one another with elegant legato.

Etude No.7 is as melancholic and wistful as étude no.1 is peaceful. Its ‘Cello’ nickname comes from the sweeping melody played by the left hand in the middle and lower registers of the piano.

Frédéric François Chopin (1810-1849)

Waltzes, Op.34

Chopin’s waltzes were not strictly designed to be danced to- they were written with the salon in mind, with nuanced shifts in tempo and dynamics.

Chopin’s Op.34 of three waltzes was published in 1838. The first in the volume was written in the summer of 1835, while Chopin was staying with the Thun-Hohenstein aristocratic family at their castle in Dĕčín, Bohemia. Three siblings within the family were students of Chopin, and he dedicated this waltz to Countess Josefina. Waltz No.1 is overwhelmingly upbeat, with a sunny opening refrain giving way to dazzling bursts of melodic and rhythmic colour. Chopin toys with the push and pull of syncopated rhythms before the waltz comes to a spirited conclusion.

While Waltz No.1 can certainly be classified as a party tune, the atmosphere of Waltz No.2 is trickier to pin down. The rise and fall of the opening melody sways with dreamlike melancholy. Waltz No.3 brings proceedings to a feverish close, bolting out of the gate with a flurry of melismatic phrases.

Program note excerpt by Stella Joseph-Jarecki.

Tickets to Jayson Gillham's Great Performers recital are selling fast. Click here to discover more and book now.

You might also be interested in

-

-

-

Explore the program notes in advance